Restructuring the static reality of Palestine

Review – Salome Chanadiri

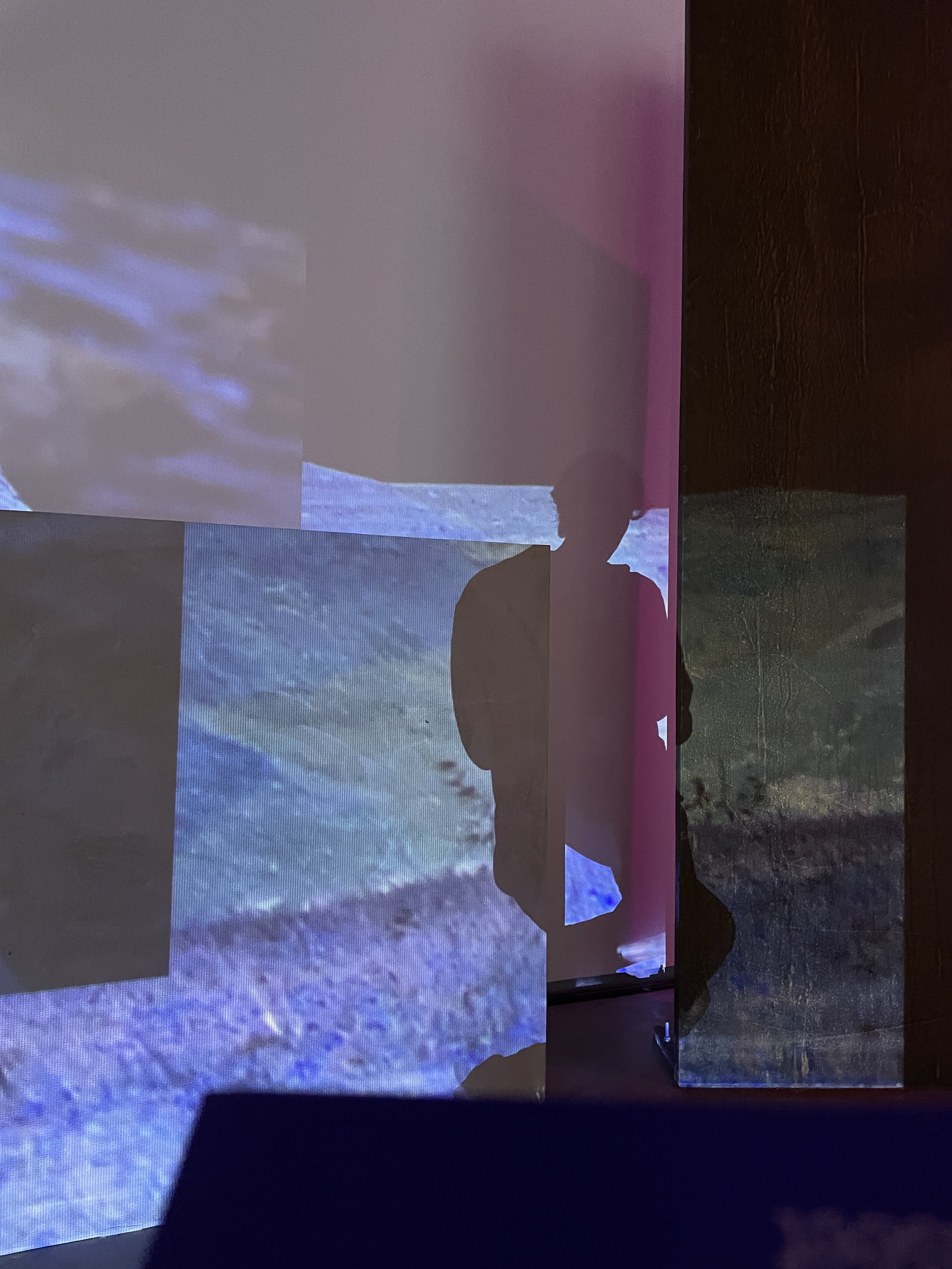

Fragmented surface with layers of video installations and a bilingual text saying „only the beloved.“ The photo is from the third room of the exhibition dedicated to the Palestinian boy killed while gathering plants for food. Photo: Salome Chanadiri / PRESSET.

Last week I went to see a famous exhibition by Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme at the Astrup Fearnley Museum in Oslo: “An echo buried deep deep down but calling still.” First, I was intrigued by the video, sound, and light installations displaying the harsh reality of the Palestinian people, but later, I left the exhibition amazed by a much bigger and a creative concept behind the chosen form.

I explored the exhibition according to the guidance of Ina Blom - a professor of the History of Art at the University of Oslo, talked to the hosts at the Astup Fearnley Museet, and noted my own experiences of seeing the artworks. As a result, here’s my review to find out why the artists chose exactly this form of representation for their concept, and how the creative video and sound installations together with lighting and physical objects serve to the creation of a new Palestinian culture.

Why 1 – Concept behind all felt and seen

The buried culture shall be reborn in a new digital form through artistic transformation. Although it sounds quite complex and even mysterious, apparently this is exactly what Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme chose as a theme behind their work – An echo buried deep deep down but calling still.

„Remember the people who started Silicon Valley era? They were deeply spiritual and thought that the human would be reborn in a digital state of mind after the physical body. I would say that these two artists [Abbas and Abou-Rahme] have this hippie feel to them. The video installations have this feeling and the hope of the human being released from soil, from culture, from war and looking towards digital.“

- Karen Nikgol, Host at the Astrup Fearnley Museet

Why 2 – Stairway to the concept

„The only things left of the destroyed villages are dried plants and some stones that are part of the ruins, so the landscape becomes a living archive itself.“

- Kristiina Veinberg, Host at the Astrup Fearnley Museet

A poem, written down in desktop notes. Screenshot print as an exhibit in room second. Photo: Salome Chanadiri / PRESSET.

Screenshots with folklore poems typed in desktop notes, 3D models of ancient masks from Palestine, and various objects from the area show the practical work behind artwork creation in the second exhibition room. But it is not only the documentation room that can be skipped to save time for „the real exhibition.“ The showroom of gathering, combining, and uniting all these materials is an artwork itself, as it not only explains how was the exhibition created but, according to my own experience, first of all, inspires the viewer to actively explore the links between presented exhibits and the actual historical reality of Palestine. You can see this room as the point where all the tips and strings are gathered to inspire new discoveries and interpretations of the artworks.

Documenting the visual content research with a screenshot print of the google images page. Exhibit from room second. Photo: Salome Chanadiri / PRESSET.

Eventually, when looking through this documentation room, you can become a creator yourself as you follow the steps of the artists and their inspiration. The exhibition after all is about inspiring new stories told through media art in a digital world:

„The artist duo don't want to give up on the Palestinian community. That's why they're creating new stories in order to find a way for the culture to live on.“

- Kristiina Veinberg, Host at the Astrup Fearnley Museet

Each exhibit in the documentation room leads to its digital counterpart: masks to avatars, poems to conceptual messages by artists, dried plants to plants in video installations, etc.

How 1 – Avatars in Video Installations

"The idea behind these video installations is to tell new narratives of an erased culture."

- Kristiina Veinberg, Host at the Astrup Fearnley Museet

A conceptual connection between the physical masks and the avatars.

The idea behind neolithic masks presented on exhibition with 3D-printed copies is “becoming other, becoming anonymous, in this accidental moment of ritual and myth,” as it is explained on a webpage of the two artists.

„If you end up in a situation with no liveable conditions, you have to find your mask, put it on and adapt. This is the only way to survive.“

- Kristiina Veinberg, Host at the Astrup Fearnley Museet

Exhibition view, Basel Abbas-Ruanne Abou-Rahme. © Astrup Fearnley Museet, 2023. Photo: Christian Øen

Apparently, the 3D-printed masks and the avatars have a common idea behind them. According to Nikgol, they both represent a person’s complex identity, but in different ways:

„With avatars you have a very modern and digital identity. Here with physical masks you have an old identity of Neolithic era, although their form is also modern as these masks are only 3D printed copies of actual masks. Of course, this is also identity, I would say, and now think of the title: And yet my mask is powerful.“

- Karen Nikgol, Host at the Astrup Fearnley Museet

So, what can this tell us about the metaphor behind the avatars?

Avatars - imperfect, incomplete, but authentic.

Bringing avatars in video installations is one way to create a new story and a chance for survival by transferring a person with a mask into a digital world. It is about the freedom of defining one’s own identity:

„an avatar is something you can't arrest, brainwash, kill, or rape. They're free. Any person is free to change avatars’ identity through computer technology. It's not preconceived for them. The text on the film is also a lot about identity and how identity is defined for us by others.“

- Karen Nikgol, Host at the Astrup Fearnley Museet

To Nikgol, the flexible identity opposes a one-sided, biased understanding of a person and refers to the recognition of their diversity and uniqueness.

„The people from the Middle East don't want to be defined as one-leveled, one-sided human beings - victims or terrorists or something else. And this is what identity in this exhibition is again a metaphor of.“

- Karen Nikgol, Host at the Astrup Fearnley Museet

An avatar with scars and bruises with closed eyes displayed in a digital frame. Real-life video shot on its background. Photo: Salome Chanadiri / PRESSET.

What made the avatars even more real and expressive was the imperfection of the algorithm that developed incomplete features on the avatars’ faces that looked like scars and glitches. As we read in the description on the webpage, „By keeping and not ‘fixing’ these visible scars the work speaks not only to the violence of the material reality but to the often invisible and embedded violence of representation itself in the circulation/consumption of images and ultimately to the violence in the algorithm.“

In those video installations, we see real-life shots in the background and the robotic acting of avatars in the front. As a viewer, I felt like the real-life images were the past-life memories of the avatars, while the avatars were presented as the new ‘real’. As if the backgrounds in the videos were telling the stories of those ‘avatarized’ individuals - as imperfect with their scars, messed-up t-shirts and repetitive dance patterns as their real counterparts.

How 2 – Backdrops of Video Installations

Fragmentation - a method and a metaphor

All the video installations are screened on fragmented backdrops of different materials like cement or wood, which fragments the videos themselves. At first sight, I associated the fragmented backdrops with a diffused identity of a lost person. On the other hand, it reminded me of the structure of memories: a mechanical combination of scattered images from the past. This interpretation could also be connected to the identity concept of the masks and avatars – the digitalizing of memories in order to create something new. In this sense, this could be seen as another method to display the concept of digitalizing identities.

During our email exchange with Ina Blom - a professor of the History of Art at the University of Oslo, she pointed to a different, genuine meaning behind the fragmented backdrop for the video installations which apparenntly relates to the historical context of Palestine:

„From my perspective, the most original aspect of the artists’ work is how the screen image is fragmented through the use of architectural elements such as the constellation of wall elements in different materials on which the image is projected. Focusing on what this does to the image and to the significance of the different wall materials - in relation to the Palestinian political and cultural context that the works reference - is, I think, a good point of departure.”

- Ina Blom, a professor of Art History at the UiO

Exhibition view, Basel Abbas-Ruanne Abou-Rahme. © Astrup Fearnley Museet, 2023. Photo: Christian Øen

Karen Nikgol revealed what the backdrops can represent as metaphors:

„I would say that these fragments of the wall of course work as a backdrop for film, but they also work sometimes as a metaphor for the wall in Palestine. But it is deconstructed.“

- Karen Nikgol, Host at the Astrup Fearnley Museet

Israel started building The Apartheid Wall or Israel’s Separation Wall in 2002. The wall cut deep into Palestinian territory and lead to the annexation of large territories and has left thousands of Palestinians without basic living conditions such as farmland, social services, and schools, writes Palestine’s Remix. If the backdrops are representing The Apartheid Wall, then maybe its fragmentation might be understood as restructuring the reality into a new matrix where the wall is not that solid anymore.

Shapes of backdrops as metaphors.

According to Nikgol, square shapes used constantly in the exhibition also refer to the complexity of a person’s identity:

„The shapes are also a metaphor of identity, I think. You see the same kind of square structure repeated all over. I believe that the square in itself is a metaphor for how one thing can be interpreted on different levels.“

- Karen Nikgol, Host at the Astrup Fearnley Museet

How 3 – Sound and silence

While video installations are eye-catching, the sounds accompanying them are dragging the viewer into a new, digital reality that fills out the whole space and creates a stronger emotional impact. The traditional motives in sound installations - texts and music - are combined with modern electronic music elements, when the texts are reshaped according to the exhibition context. As in video installations, there is repetitiveness in song lyrics as well. Alliteration and refrains put pressure on the viewer’s senses but also bring out very important messages for understanding the concept behind every exhibit.

Dynamism in a static reality

There is an intensive dynamism in music, as well as in video installations, which contrasts with the static reality of Palestine. This dynamism is a depiction of not giving up, and of clinging to the chance of survival in a new form, and in another - digital - reality.

Exhibition view, Basel Abbas-Ruanne Abou-Rahme © Astrup Fearnley Museet, 2023. Photo: Christian Øen

Silence is also a big part of the sound installation. Usually intensive music is followed by a silence that accompanies contrastingly dynamic video installation. As a visitor, I got the feeling that such shifts from dynamism to staticity in music represented a person's mindfulness in which the inner screams give way to the deep focus and internalized vision (that you might recognise from Munch’s Skrik as well).

In a way, the exhibition is interactive.

The lighting, the colour palette in different rooms, and of course the positioning of screens in exhibition rooms create a virtual space experience, dragging the viewer into the dynamic exposition. Although there's no physical contact with the exhibits, the viewer's distinct shadow appears on screens while moving around in the room between the installations. Seeing your silhouette gives you the feeling that you are another character in video installations, and creates a different kind of emotional interaction or bond between you two. It feels like saying, „All this is real after all because I am here, and I feel it“ and that is why, in my point of view, the effect follows you outside the exhibition rooms as well.