Korean cinema on the world stage

Interview - Hanna C. Nes

Darcy Paquet’s presentation on Korean crime films.

Photo: Hanna C. Nes / PRESSET.

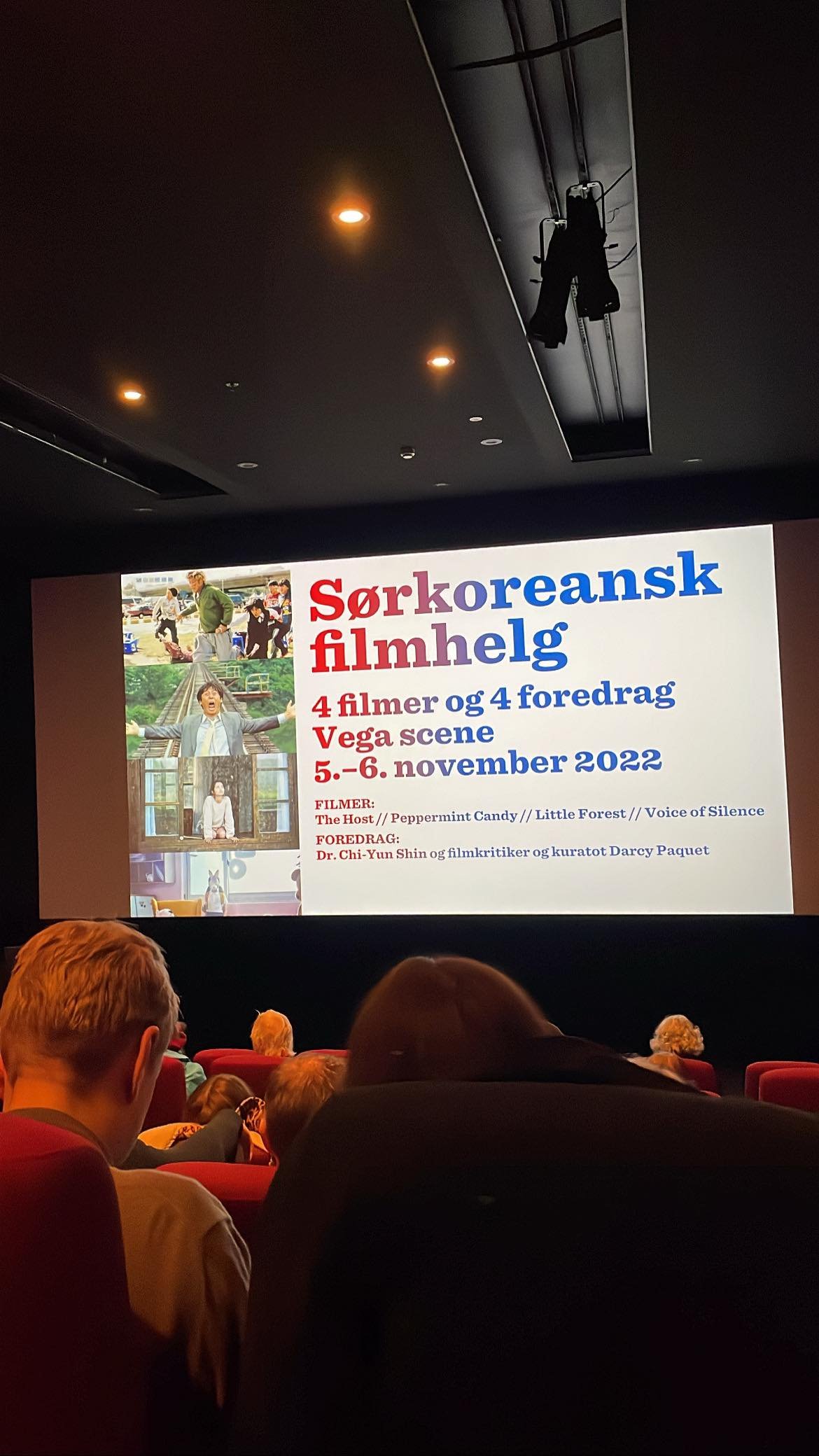

On November 5th and 6th, Norsk Filmklubbforbund held their annual film seminar at Vega scene, a weekend packed with screenings and talks from visiting experts. This year’s theme was South Korean cinema, featuring presentations from lecturers Darcy Paquet and Dr. Chi-Yun Shin.

I had the pleasure of attending Sunday's programme, which included talks and screenings of the touching Little Forest (followed by a delicious crème brûlée snack) and the heart-wrenching crime drama Voice of Silence. The cinema was packed with audience members of all ages, brought together by their curiosity and love for international cinema.

Following the day’s activities, I got a chance to sit down with Darcy to chat a bit about his work and the current landscape of Korean cinema. Darcy Paquet is an academic, film critic, author and translator living in Busan, South Korea. After starting his career in the late 1990s, Paquet has been instrumental in South Korean cinema’s international explosion, serving as the subtitle translator for Parasite and the newly released Decision To Leave. He published his book New Korean Cinema: Breaking the waves in 2009 and is a big fan of Memories of Murder. Check out our conversation below!

This interview has been edited for clarification.

A chat with translator and writer Darcy Paquet at the Norsk Filmklubbforbunds annual film seminar .

How did you initially get into Korean film?

– It started as a hobby. So I had come to Korea as an english teacher and I was interested in the country because I had a lot of Korean friends in grad school and I wanted to learn the language. I was a fan of Asian cinema but didn’t know anything about Korean cinema. I just started watching some films and they were really interesting so I’d go online and I’d look for information about them and there’d be nothing in English. In the end, I decided to make a website just as a hobby and to put up reviews of the films that I had seen so that at least it was up there (laughs). And it was right at the time - I mean, this was 1999 - it was just when Korean cinema was starting to grow and people outside Korea were starting to take notice of it. So my timing was perfect. After a couple years. I had an offer to work as a journalist so at that point I quit teaching and for seven or eight years I worked at writing news about the Korean film industry.

So when did you shift that into also doing translator/subtitle work?

– It started fairly early and initially it was mostly proofreading. Working as a journalist, I was meeting a lot of companies and so I got to know them. If they received a translation they weren’t happy with, sometimes they’d ask me to polish it. Later, I started co-translating with a friend of mine who’s a filmmaker but who speaks English very well so we would sit down together in front of the TV and work on subtitles.

Those must have been very long watch sessions (laughs).

– Yeah it took a long time. As time went on, I slowly did more and more. It was about 8 or 9 years ago that I decided to get more intensively involved. At that point my Korean was good enough that I could do the rough draft myself. People still check my work and give me lots of feedback. I’m doing a lot of translation these days.

Would you say that translation work is a very collaborative process? I feel like there’s an idea that it’s usually just one person doing it and it’s their version.

– I think it helps a lot if it is collaborative. It can be a problem if there’s too many people in control and everybody’s changing what everybody else is writing and then you get a mess. Feedback is tremendously helpful because there’ll be things that didn’t occur to me that if somebody else suggests it might be perfect for this problem that I’m trying to solve.

I saw you recently had an interview in Forbes and you made a comment there that now since Korean cinema’s really exploded in the mainstream zeitgeist, especially after Parasite, that for a lot of directors maybe the international audience is more on their mind. How has that changed the approach to translation work?

– On a practical level it means things often need to be translated before they’re made, like the screenplay, treatment or a long description of the plot because often they’re looking for finance abroad as well as in Korea. When translating, I’ve always been really conscious of the international audience so it hasn’t changed that much for me with the actual translation work. However, the one thing is that people are more familiar with Korean culture. 20 years ago if I found the word “soju” in a line of dialogue, often then the company that hired me would ask me to change it to something else cause they were worried people wouldn’t know what it was.

Find an equivalent of a sort?

– Yeah, which is always really awkward (laughs). Sometimes you can just say booze or alcohol, you could say “rice wine” but it’s not “rice wine”.

I really enjoyed your talk about crime as a genre in Korean cinema, especially as someone who doesn’t have much familiarity with the crime genre. I was wondering what’s your take on the main points through which the Korean crime genre differs from the Hollywood crime genre? You touched upon this element of realism, if you want to expand on that?

– I’m not sure how well I can back up this statement but I think that, at least looking back a little bit, because Korea went through this long period of time with strict censorship where the moral messages of the films had to be very clear and simple, I think the generation that came after that, which is Bong Joon-ho and Park Chan-wook, they were attracted to really complex moral quandaries. Partly in reaction and partly because it was possible to make these films now without having to get approval or getting it past censorship. That became a part of Korean cinema’s identity to a certain extent. So younger directors learned and were really influenced by the previous generations so they’ve created these traditions. A movie like the one we just saw, Voice of Silence, we’re pulled in many different directions and we’re not sure what to feel about the main character. He seems like a decent person who’s in a bad situation and the little girl as well at the end…

It’s quite visible the shift in her. She’s amazing.

– Certainly there are exceptions in Hollywood but I think Hollywood is a bit more streamlined although you get movies like the Coen Brothers, they’ve been doing this thing as well.

The first half of the film I was thinking of Raising Arizona just with the really odd tonal shifts. Going off of that, I was wondering since you showed a clip from the film The Day Off [from 1968] and part of me was like “this feels like Breathless”...do you see a lot of influence from New Wave movements on Korean cinema just in terms with the moral ambiguity, these odd tonal choices from directors in this genre specifically?

– For the older directors it really depended on the person because some of them tried to follow new trends in international cinema. For me the director it really reminds me of is Antonioni, partly the cinematography and the mood, and how we’re not really sure of what the characters are going through. In contemporary times, a lot of Korean directors, similar to Tarantino, watch a lot of films and are influenced by a lot of films. I showed a clip from A Bittersweet Life (2005) and if you ask director Kim Jee-woon who his favourite director is he says Robert Bresson and he makes movies nothing like Robert Bresson (laughs). He’s a cinephile, he loves films of many different types so sometimes the endings in his films, it’ll be a really commercial film but the ending doesn’t feel conventionally satisfying and resolved and I think that’s his love of arthouse cinema having a bit of an influence on his commercial stuff.

That feels very clear even in just the opening of that movie with the very spiritual quote. It feels totally out of place in a “conventional” version of that [film]. I was very pleasantly surprised that this film [Voice of Silence] was a female director [Hong Eui-jeong] and also her feature film debut. What has been the representation and support for female Korean directors in these traditionally hyper-masculine genres?

– It’s slowly changing but there’s still a lot of issues that need to be solved. In the case of this film, she happened to meet a producer who had enough influence to get this film made. He believed in her story. You do hear cases of women who maybe they have an idea of something in their mind of something black or unusual and they’ll be told well why don’t you make a more conventional drama first and then you can make that as your second film. No male director would ever be told that. The big difference is with big budget films and it’s really rare for women to get the opportunity to direct a big budget blockbuster. That’s definitely unfinished business with the film industry. In one sense, a lot of progress has been made as the numbers are much better than they were 10 years ago. You regularly have women directing films in a wide variety of genres and this was one example.

Was this an indie production?

– No, it wasn’t a big budget film, it was slightly below average for a commercial film but the gap between indie film and commercial film is really big.

You also mentioned that everyone knows about the established Korean auteurs internationally, have you noticed an uptake in international streaming service support or festival support for indie filmmakers in Korea?

– The support for indie filmmakers is partly from the government and in that case it depends on who’s in power (laughs). When the Conservatives are in power, the money goes down, and when the Progressives are in power, it goes up. These days a lot of film schools are trying to give opportunities to their graduates to make feature films so many of them have funds so if your film is selected for that fund, they’ll have maybe 300,000 USD to make a low budget feature film. Apart from that, there are a few other sources of finance but it’s kinda hard to get at.

One final question for you, if you had to give someone who’s not very well versed in Korean cinema two or three movies to just start out with, what would they be?

– One called New World, it’s a gangster movie. If someone likes The Godfather, I’d recommend New World. There are ways in which the movie kind of stole from The Godfather (laughs) but it’s a well made film. It has Lee Jung-jae, the lead from Squid Game. There’s a movie called The Chaser which is more of a thriller and based on a really disturbing real-life case of man who murdered several people and buried them in his backyard in a neighborhood in Seoul.

Sounds like nice family viewing!

– That movie is so intense. You have some thrillers that are emotionally intense and others not so much. This one is so intense and you want to shout at that screen and warn the people to run away (laughs). And something that’s kind of fun…The Thieves is a very cleverly plotted story about this theft casino so that’s a fun film to watch!

Many thanks to the Norsk Filmklubbforbund and Darcy! You can check out their programming at filmklubb.no for other interesting events, as well as Darcy’s work on Twitter at @darcypaquet

Read our other articles and interviews from prior filmseminars at Vega Scene hosted by Norsk Filmklubbforbund:

Den kvinnelige hevneren på film – filmseminar på Vega Scene

Minnevirkelighet i art cinema – filmseminar på Vega Scene